Destination Stewardship Report – Autumn 2023 (Volume 4, Issue 2)

This post is from the Destination Stewardship Report (Autumn 2023, Volume 4, Issue 2), a publication that provides practical information and insights useful to anyone whose work or interests involve improving destination stewardship in a post-pandemic world.

[Above: The 12 Apostles sea stack formations, a highlight on the Great Ocean Road, visible at top of frame. Photo: Jonathan Tourtellot]

Architectural Tactics for Dispersing Tourism: Lessons from Australia’s Great Ocean Road

In the idyllic landscapes along Australia’s famed Great Ocean Road, the economic and social impact of architectural interventions has become a focal point, addressing the dearth of accommodations in the inland regions. The challenge of attracting tourists to these areas while strengthening the local communities unveils compelling success stories in three distinct domains: the towns, the hinterlands, and a thematic trail. Amidst this exploration lies a crucial lesson: the renovation of small town centers and innovative repurposing of buildings can revitalize these regions, preserving their heritage and bolstering local economies. Clara Copiglia tells us more.

Inspiration along the Great Ocean Road

Back in September 2018, I embarked on a weekend trip to the renowned Great Ocean Road, a scenic drive along the south coast of Victoria, Australia. Due to our modest budget, my partner and I opted for an overnight stay away from the seashore. As night descended, we journeyed an hour north from the coastline and found the inviting glow of the Mount Noorat Hotel, the sole source of warmth and light in the tranquil rural darkness. We were the only tourists staying in the hotel that night, and during our short visit, we learned from the hotel’s owner that it was the only place left in the area for local inhabitants to meet and for tourists to sleep.

From that day on, I was determined to understand the economic and social impact of places like this hotel. Were there others?

A map of the research area. The red dots represent points of interest for visitors such as hotels, restaurants, lookouts, and recreational areas. [Map courtesy of Clara Copiglia]

At the beginning of 2023, two years after completing my architectural degree, I returned to this area to study renovated buildings located inland that impact visitor numbers. You can download the complete report as a pdf.

Here are examples from the research, focusing on success stories and organized in three parts: The towns, the hinterland, and a thematic trail.

The Inland Towns

As most visitors travel by car or tourist coach, they will likely pass through many regional towns and see their streetscapes, usually composed of storefronts and hotels. Originally, storefronts were food shops, blacksmith shops, bakeries, etc., while hotels provided accommodations for visitors and a pub. Today, many storefronts are abandoned or have been converted into private houses, and many hotels are closed.

The historic Mount Noorat Hotel, built in 1909. [Photo courtesy of Clara Copiglia]

The Mount Noorat Hotel had been renovated first by the previous owner, who I met back in 2018. He took off the fake ceiling and repainted the interior, giving it a warm atmosphere. On the second floor, the hotel has a few well-renovated rooms that bring travelers to Noorat who discover the area or visit relatives. Aided by some local-government funding from Corangamite Shire, the Blain family has taken over the renovation and plans an outdoor seating area.

Lesson learned: In small regional communities, there is often a space that can both serve as a gathering place for locals and host visitors. It is essential to identify these types of buildings and care for them. In the case of Noorat, the hotel is kept open thanks to devoted locals and government help.

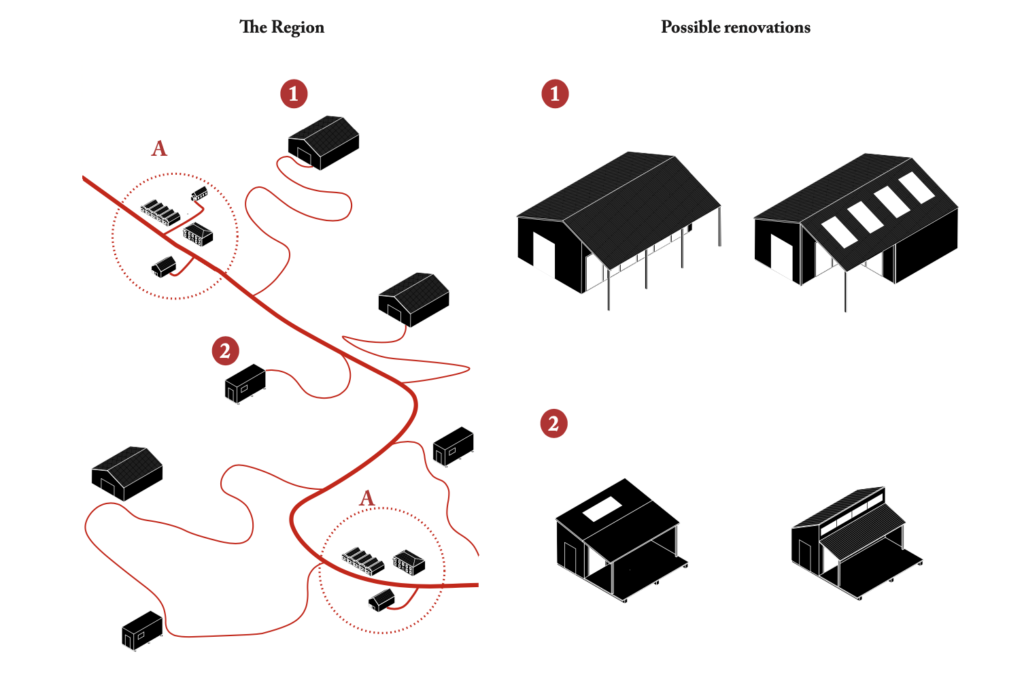

In other towns in the area, in addition to hotels, these buildings might include converted churches, storefronts, halls, etc. There are many simple ways to upgrade those spaces like adding openings, creating an outdoor covered space, which would transform it into a welcoming place for both community and visitors. Storefront establishments, for instance, can gain appeal by sprucing up the façade and adding skylights or a back terrace.

The Hinterlands

In between the towns inland from the Great Ocean Road, the landscape varies from tropical forest to plains punctuated by extinct volcanoes, lakes, and farms. But relatively few visitors come compared to the seashore.

The remarkable tiny house, ‘Stella the Stargazer’, with its clever design and unique amenities. [Photos courtesy of Brook James and Greta Punch]

Stella was moved every eight weeks to different locations in Victoria, including the Great Ocean Road region. The tiny house is placed on farm properties to highlight the natural landscape, and a chef collaborates with locals to provide visitors with food products from the area. The farmers get paid rent and don’t have to manage the bookings.

Stella was mostly built with reclaimed materials; its truss and cladding come from an old local farm shed that Ample dismantled. Stella is entirely off-grid with solar panels; it can harvest rainwater, and the grey water goes into into holding tanks. Nothing is left on-site.

Lessons learned: Having the tiny house as an accommodation for tourists is a great opportunity for a second revenue stream for locals by bringing visitors to areas outside towns. It offers visitors a chance to stay in a natural landscape while connecting with local residents with products to share.

Thematic Trail

To connect town centers on the coast with businesses in the hinterlands, the ‘Gourmet Trail’ grew from adaptive re-use of an old building.

Two local dairy farmers, Caroline and Tim Marwood, converted an abandonned railway shed in the town of Timboon into a distillery. They created an extension, added large windows and an outdoor seating space.

Family-owned Timboon Distillery specializes in single malt whisky. [Photo courtesy of Clara Copiglia]

After the renovation of the railway shed, local producers started formalizing an itinerary between the Distillery and other production places, such as a cheesery and a winery. The idea was to promote each other’s products, make visitors stay longer, and disseminate visitation in the area. The main support for extending visitor reach is a map distributed in visitor centers and all gourmet trail businesses.

A diagram mapping the buildings in the Hinterlands area and possible renovations. [Photo courtesy of Clara Copiglia]

The businesses in rural areas on the Gourmet Trail repurpose commonly found types of buildings on farms, such as metal sheds, converting them for tourism activity. For example, the latest member of the Gourmet Trail is Keayang Maar Vineyard, located between Cobden and Teerang. The building has one part for storage and another for wine tasting. You can see this dual use in the shape of the building, which shows a large and high space on one side, and the form of the roof adapt its shape to create a covered outdoor area for visitors.

Lesson learned: The Gourmet trail works well because creative renovation of old buildings combined with local products helps entice tourists to detour inland from the popular Great Ocean Road. Some of these businesses also provide new meeting spaces for locals.

Conclusion

My research area covered two shires. I found that renovating buildings in small town centers, such as hotels, storefronts, and standalone buildings, is crucial for attracting tourism and combating depopulation. This investment can help create a more vibrant atmosphere, preserve historic landmarks, and boost the local economy.

In the rural hinterlands farmers and entrepreneurs can introduce new buildings, such as tiny houses for tourists, or work with the existing metal shed landscape by introducing new purposes for this common building.

While working on this project, I stayed at the Mount Noorat Hotel – one of the first guests to book a room for a longer stay. While talking with some of the locals in the Hotel’s pub one evening, I heard the rumor that the abandoned butter factory near the center had found a new owner. I wonder what the plan is for this building and if it will bring more visitors to Noorat? Will it serve the community? An opportunity awaits.

About the Author

Clara Copiglia has an MSc in architecture from ETH Zürich. These past few years, she has focused on bringing together sustainable tourism and architecture to revive destinations and support local communities.