Destination Stewardship Report – Autumn 2023 (Volume 4, Issue 2)

This post is from the Destination Stewardship Report (Autumn 2023, Volume 4, Issue 2), a publication that provides practical information and insights useful to anyone whose work or interests involve improving destination stewardship in a post-pandemic world.

Swimmers enjoy a hot-spring warmed ocean inlet amid cooled lava in the Azores Geopark. Photo: Jonathan Tourtellot

The Surprising Value of Geoparks

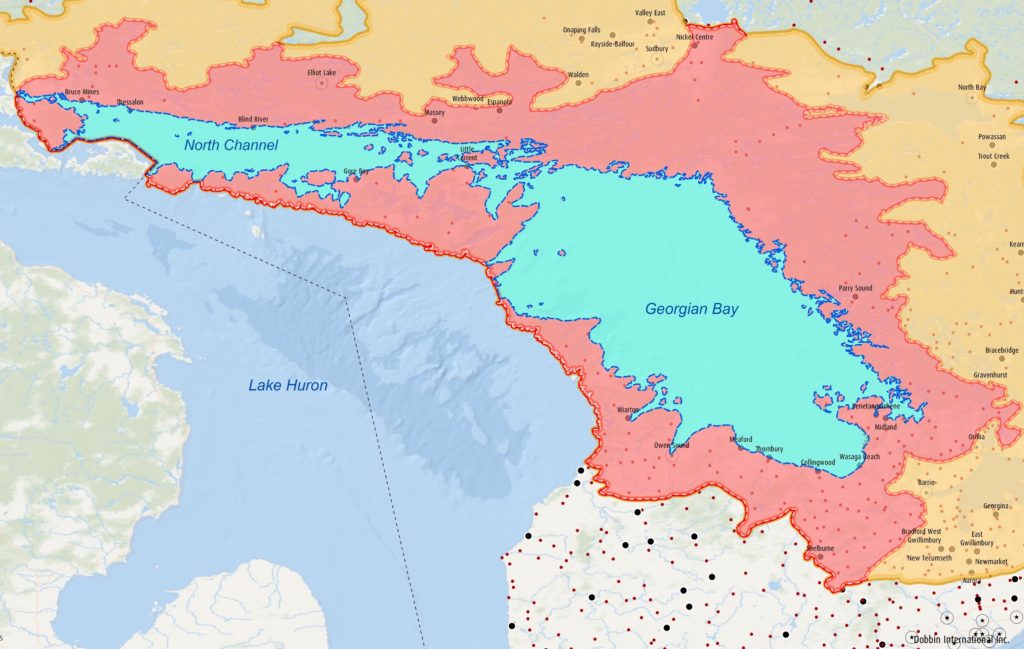

All around Canada’s northern Georgian Bay, an intriguing proposal is stirring both local and international interest. Tony Pigott, a retired J. Walter Thompson executive, is leading an effort called then “Aspiring Georgian Bay Geopark,” aiming for the coveted UNESCO geopark designation. But what is a geopark and how can it promote destination stewardship? Jonathan Tourtellot, CEO of the Destination Stewardship Center, explains.

The prestigious UNESCO designation is not what you think.

The pink-colored zone represents the proposed geopark around Georgian Bay, Ontario. [Photo courtesy of Dobbin International]

Rocks.

He’s addressing a meeting in Killarney, Ontario, Canada, convened to present the idea of an “Aspiring Georgian Bay Geopark” to interested citizens. His audience lives around the northern part of that Bay, the vast, island-studded body of water attached to Lake Huron.

Pigott, a retired J Walter Thompson executive, is spearheading the Geopark bid. The proposition is that a UNESCO Geopark designation could improve tourism in a region that needs it, especially for the numerous indigenous communities around the Bay.

To a geologist, Giant’s Tomb Island is a drumlin. It lies out in the Bay, an oval mound of glacial drift deposited thousands of years ago under flowing ice. But to the local Anishinabek people, it is the sacred resting place for the giant god Kitchikewana, who was big enough to guard the whole Bay. (More of his story shortly.) Geopark advocates call this dual point of view “two-eyed seeing.” It’s essential here for assuring equal time for both Western scientific and local traditional perspectives.

The profile of Giant’s Tomb Island resembles the shrouded body of the great god Ketchekewana. Photo: Mike Robbins

What Are Geoparks?

The first time I heard of geoparks, I pictured some kind of interesting rock formation, perhaps a few hectares in area, protected by a fence.

Wrong.

For one thing, they aren’t usually parks at all, although some form of protection is necessary for the UNESCO nod. A geopark is a geographical designation that might cover a large area. The entire Azores archipelago is a geopark (main feature: volcanoes). And while some geological attribute of significance is required, the mandate steers closely to the holistic concept underlying good destination stewardship. According to the UNESCO website:

UNESCO Global Geoparks are single, unified geographical areas where sites and landscapes of international geological significance are managed with a holistic concept of protection, education and sustainable development. Their bottom-up approach of combining conservation with sustainable development while involving local communities is becoming increasingly popular. [My italics.] And:

While a UNESCO Global Geopark must demonstrate geological heritage of international significance, the purpose of a UNESCO Global Geopark is to explore, develop and celebrate the links between that geological heritage and all other aspects of the area’s natural, cultural and intangible heritages. [My italics.]

Killarney’s St. Bonaventure church is built of gneiss, quartzite, and feldspar, each with a story from deep time, eons before Ontario existed. [Photo by Jonathan Tourtellot]

Background

The geopark movement grew from a 1991 symposium of Earth scientists concerned about growing risks to important sites. Europe hosted the first geoparks. In 2004 the 17 existing European geoparks joined with 8 new Chinese geoparks to form a Global Geopark Network under the auspices of UNESCO. It grew to a membership of more than 100 geoparks around the world and prompted creation of a Global Geoparks Council, appointed by the UNESCO director-general, to vote yay or nay on new applications, starting in 2016.

The initial impetus for these types of UNESCO programs has been the goal of protecting and celebrating their stated raisons d’être. Just as Biosphere reserves focus on biodiversity, World Heritage sites on history and nature, and Intangible Heritage on cultural practices, so do Geoparks focus on geological heritage – “the memory of the Earth,” as geologists call it.

For many if not most of these programs, preservation for its own sake doesn’t secure sufficient political support, so advocates achieve success by dangling the carrot of tourism in front of government bodies.

Rarely does the carrot come with instructions. That may result in overtourism in affluent accessible places, undertourism in needy remote ones, or simply missed opportunities. So UNESCO now requires a geopark to have a holistic, national-government mandated management body in order to win its stamp of approval. (Oddly, the geopark movement has yet to gain traction in the United States, possibly due to lingering right-wing suspicion of anything beginning with “UN.”)

How To Become a Geopark

A volcanic vineyard: Stonewalls made of lava protect grape vines from Pico Island winds, Azores Geopark. [Photo by Jonathan Tourtellot]

- Management by a body with legal recognition under national legislation;

- Participation in the management body by all relevant stakeholders, including partners and scientific, local, and Indigenous (if any) communities;

- Means of connecting the area’s geological heritage with its cultural and natural heritage;

- Engagement in appropriate branding, visibility, and communication efforts extended to both visitors and local people;

And more.

Approval by the Global Geoparks Council is known as receiving a “green card,” good for four years. Then the Council requires revalidation. If conditions have deteriorated, the geopark receives a “yellow card,” requiring that it take remedial steps within two years. If there’s inadequate improvement, it loses its UNESCO status – the “red card.”

“UNESCO Global Geoparks are living, working landscapes where science and local communities engage in a mutually beneficial way.” – UNESCO

The Aspiring Georgian Bay Geopark still has a long way to go for its green card, especially given its size and the 40+ Indigenous communities (First Nations and Métis Councils) scattered around it. Organizers were disappointed that only one Indigenous person showed up for the Killarney meeting. Still, the project leadership seems smart, dedicated, and in it for the long haul.

Indigenous Heritage

Their daunting task seems suitable for, well, a giant god. The story of Kitchikewana, however, does not end well.

Rebuffed in love, so goes the tale, Kitchikewana grew so angry that he grabbed up great gobs of earth and rocks, casting them across Georgian Bay and so creating its 30,000 islands. He then died of a broken heart, and the profile of his body can still be seen today: Giant’s Tomb Island.

Hmm. If you substitute “glacier” for the rampaging Kitchikewana in that story, you’ve got a pretty good characterization of what the melting ice sheet left behind.

Seems a lot like two-eyed seeing.

About the Author

Jonathan Tourtellot is the CEO of the Destination Stewardship Center; Editor of the Destination Stewardship Report; Principal of Focus on Places LLC; Founding Director of the former Nat Geo Center for Sustainable Destinations